A Diaspora Haunted by Disinformation

Photo by Jennifer A. Ortiz for Feet in 2 Worlds. Photo collage by Yunuen Bonaparte/palabra

Listeners of Spanish-language radio in the U.S. face a growing threat from misleading and false information, as experts warn of its potential impact on the Latino vote in the upcoming elections.

Editor’s note: This story is part of Frequency of Deception / Radiofrecuencia de engaños, a six-part series by Feet in 2 Worlds in partnership with WNYC’s Notes from America, palabra, and Puente News Collaborative on the spread of dis- and misinformation on Spanish radio in the U.S.

This radio piece was produced by Feet in 2 Worlds in collaboration with WNYC’s Notes from America.

Haz clic aquí para leer este reportaje en español.

Valeria Polonsky is worried. Polonsky, a Latina who has lived in the Miami area for the past 20 years, is concerned about the presidential election — particularly the lack of dialogue between people on opposing political sides. She sees it in her own circle of friends. One friend sends her messages about how the 2024 election will be stolen and other narratives that sound like unproven conspiracies.

“My best friend — I love her, I do — but well, it’s like she gives me a little extra insight that you obviously wouldn’t say to someone you weren’t close to,” says Polonsky. "And sometimes I’m like, 'Wow, where did that come from?' She’ll say, 'They’re going to steal the election, this is going to happen, that is going to happen…' So I ask her where she gets this information and she says, 'From my family, everywhere.'"

Polonsky is not alone in worrying about the impact of false information on the outcome of the upcoming election. From a U.S. Senate candidate in Florida who fields similar texts from her friends to a 24-year-old organizer in Las Vegas whose dad asks him to verify the memes he’s getting, Latinos across the U.S. are watching their friends and relatives hear, read, and share misinformation and disinformation.

Polonsky spoke as she waited for her car to be washed at a gas station in Weston, a suburban community 30 miles northwest of Miami with a large Venezuelan and Colombian population. She was sitting on a hot concrete bench while people pumped gas behind her and customers walked in and out of the cafeteria selling empanadas.

The local gas station and fast-food chain is called PANNA, after a Latin American term for “friend.” Polonsky was very friendly herself as she answered questions about what media she gets her information from — CNN and NPR.

Panna New Latino Food, a Venezuelan restaurant located in a gas station in Weston, Florida. Weston is nicknamed "Westonzuela" due to its large Venezuelan diaspora. “Panna” is slang for friend in a few countries in Latin America, including Venezuela and Cuba. Photo by Jennifer A. Ortiz for Feet in 2 Worlds

Miami is often called the “gateway to Latin America.” The city’s immigrant residents have brought their cuisines, their accents, and their media consumption habits to everyday life in South Florida. Many Latinos are long-accustomed to getting news and information from the radio. But the trust that Latinos have in radio is increasingly being tested, as domestic and foreign broadcasters fill the airwaves with misleading and false information.

While misinformation and disinformation are shared in many languages and aimed at many audiences, they target Spanish-speaking radio listeners in specific ways that have caused alarm among academic researchers and political activists.

Many radio stations and radio hosts that serve Latino audiences remain committed to broadcasting information that is true and factual. But there is growing concern this election year that Latino voters may be making decisions at the ballot box based on information that is incorrect or deliberately inaccurate.

On “El Show de Jorge Bonilla,” a conservative talk show in South Florida, listeners in June were told that the Biden administration’s border policies led to a rise in violence. Bonilla, the host, repeated a misleading claim that President Joe Biden opened the border, implying that immigrants crossing the border illegally are murdering women in the US. On another show a host falsely claimed that an abortion rights amendment on the November ballot in Florida would allow tattoo artists to perform abortions.

Latinos are the second fastest-growing group of voting-age Americans in 2024; an estimated 36.2 million Latinos are eligible to vote this November. In some places where the margins are narrow between candidates and on issues, Latinos could cast deciding votes.

Disinformation is amplified when it shows up on the radio and in other traditional news media, according to Josephine Lukito, a professor at the University of Texas at Austin's School of Journalism and Media. Lukito uses computational and machine learning methods to detect and monitor misinformation and disinformation, both foreign and domestic.

“It's one thing if an average Twitter (now known as X) user or even … a family, or friend, member on WhatsApp shares a link or a piece of misinformation,” Lukito noted. “It's a totally different story when a radio show or a news organization or a politician shares it, because their reach is so much larger.”

Hispanics in the U.S. come from a tradition of listening to radio in their home countries, explains Adelys Ferro, the executive director of the Venezuelan American Caucus, an immigrant advocacy organization in Miami. “Believe me, radio really is listened to a lot,” Ferro said. “And back then, when you listened to someone reading the news, you took for granted (that it was true). I took that for granted in Venezuela.”

Pete Hernandez serves patrons fruit and fresh juices while listening to Radio Libre at his store in Little Havana, Miami, Florida. Photo by Jennifer A. Ortiz for Feet in 2 Worlds

Ferro’s group is part of an umbrella non-profit organization called Latino Victory that supports progressive Latino candidates and causes. She spends a large part of her day listening to Spanish-language radio, monitoring stations for misinformation and disinformation. “It’s extremely discouraging to know that there are so many people being influenced by totally false content,” she lamented.

According to the audience measurement company Nielsen, radio reaches 94% of Hispanic adults, compared to 90% of the general population. A Pew Research study conducted in late 2023 found that half of all Hispanic adults in the U.S. say they at least sometimes get their news from Hispanic news outlets. These can be in English or Spanish, but they are media outlets that specifically target Latino consumers.

WANT MORE INVESTIGATIONS LIKE THIS?Help palabra dig deep into the stories that matter to you. Donate today! |

More than half the residents in Miami-Dade County are foreign-born, and Hispanic immigrants are much more likely than U.S.-born Hispanics to get news from Hispanic outlets. That news includes updates about their countries of origin, such as Colombia, Venezuela, Nicaragua, and Cuba.

When it comes to Spanish-language media, some of the most influential Hispanic outlets broadcast from Miami. Telemundo and Univision are the top two TV networks in the U.S. in Spanish. There are at least 13 radio stations in Miami that broadcast in Spanish; many belong to networks that operate stations around the country. Nationwide, there are twice as many Hispanic radio stations as there are National Public Radio network affiliates.

Not all stations air disinformation. Many Spanish-language radio stations broadcast entertaining, informative, and community-centered information. A scan of the car radio on any given day will offer up a Bad Bunny song, current events in Colombia and talk show hosts quoting the Bible. A caller on conservative talk radio applauds right-wing, populist presidents in Argentina and El Salvador for “recovering democracy” as he discusses U.S. politics.

But Ferro said she often hears disinformation on some South Florida stations, like the claim that people crossing the border into the U.S. are responsible for a wave of crime. That narrative reaches other immigrants, like Cubans who listen to conservative radio stations in Miami. The effect, she said, is that, “those same people reject their own immigrants.”

A truck in Miami with pro-Trump and Cuban stickers. South Florida is home to the largest Venezuelan, Nicaraguan and Cuban communities in the U.S. Photo by Jennifer A. Ortiz for Feet in 2 Worlds

It can be difficult to track where disinformation originates. Many U.S. Latinos receive news and information from sources in the U.S. as well as from abroad. According to Lukito, misinformation can spread through interpersonal communication, “and that includes family both within the United States and outside of the United States.” The false messaging itself can cross borders. Lukito said that as of May 2024, she’d already seen election fraud claims appear on social media in English, Mandarin and Spanish.

“All of those strategies are flowing from one country to another,” said Lukito. “It informs the way our parents vote and (how) they think about the safety of elections, both in our home countries and in the United States.”

There have been presidential elections this year in several Latin American countries, including El Salvador, Panama, Dominican Republic and Mexico. In Venezuela, authoritarian President Nicolás Maduro ran for a third term and declared victory in July, despite allegations by the opposition and the U.S. State Department of election interference.

Adelys Ferro said that there’s one country in particular that benefits from spreading disinformation that jeopardizes democratic elections around the world. “Technology experts, not politicians, tell you that it comes from Russia,” she said.

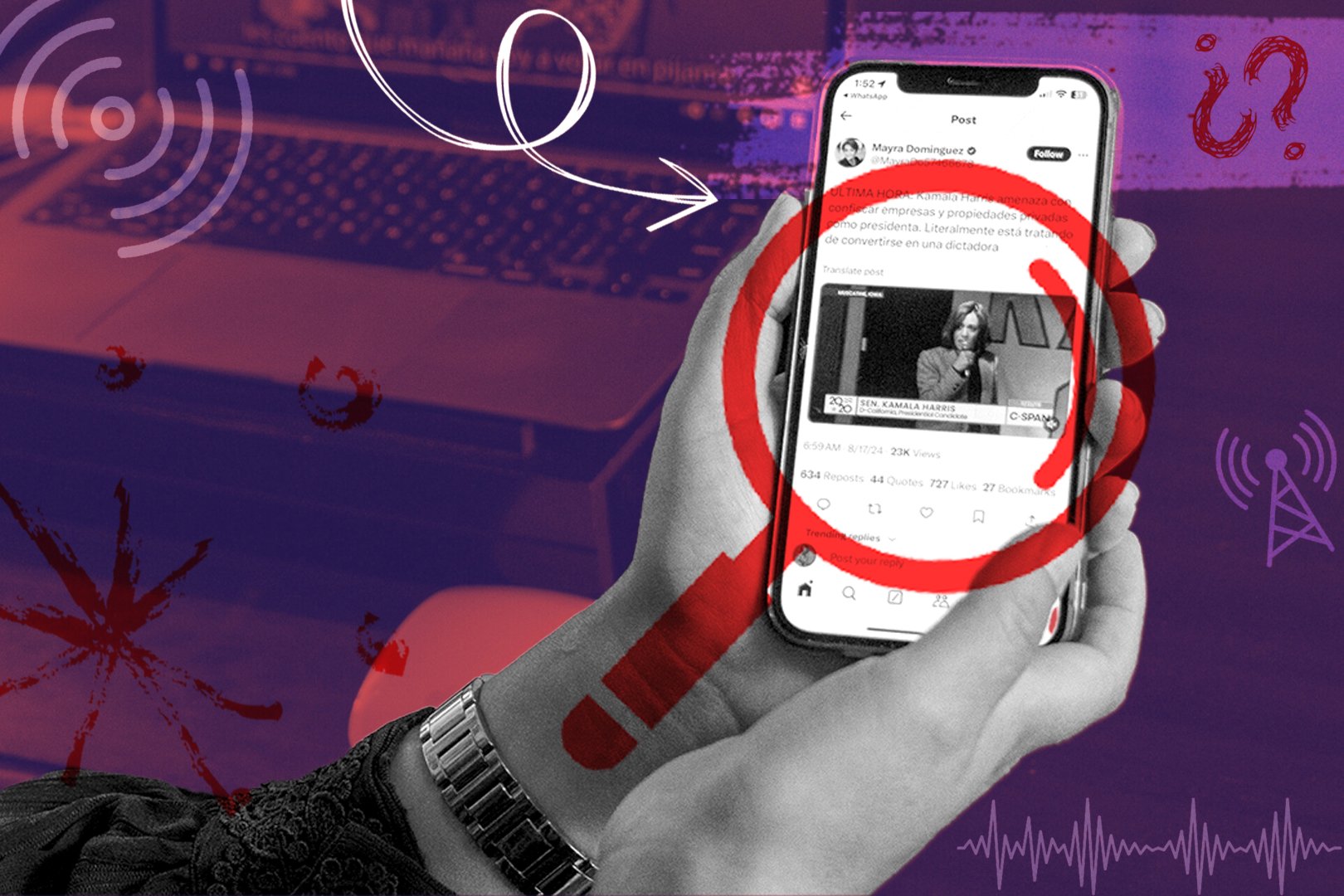

Evelyn Pérez-Verdía shares an example of Spanish language misinformation linking VP and presidential hopeful Kamala Harris to Communist world leaders. Pérez-Verdía is founder of We Are Más, a South Florida-based social impact organization specializing in culturally competent, multilingual hyperlocal engagement with diaspora groups. Photo by Jennifer A. Ortiz for Feet in 2 Worlds

Russia has used disinformation to undermine U.S. interests since the Cold War. RT, formerly called Russia Today, and Sputnik, named for the first Soviet-era satellite launched into space, are longtime Russian outlets that own or influence proxy outlets all around the world. These include radio networks, newspapers, blogs, YouTube channels, and social media accounts. According to the U.S. State Department, these outlets “serve as means for the Kremlin to disseminate disinformation and propaganda narratives to audiences outside of Russia.”

Latin America is no exception. Spanish is the fourth most spoken language in the world. Radio Sputnik produces broadcasts in Spanish from Latin America. And Spanish-language social media accounts related to the Russian state help spread false narratives in Latin America intended to sway public opinion on topics important to the Kremlin, like the war in Ukraine.

This article is part of U.S. Democracy Day, a nationwide collaborative on Sept. 15, the International Day of Democracy, in which news organizations cover how democracy works and the threats it faces. To learn more, visit usdemocracyday.org.

|

In October 2021, an independent think tank called Global Americans found that Russia, China, and other “non-democratic actors” have used state-sponsored media to spread disinformation on Twitter (now known as X) and Facebook in Mexico, Colombia, Argentina, Chile, Peru, and Venezuela.

According to the Brookings Institution, in April 2022, RT en Español was the third most shared account on Twitter giving out information in Spanish about the war in Ukraine. These included Russian affiliated government accounts in Spanish, like the Russian Embassy in Spain. In one particularly sinister example, the report found that Russia was using “authentic influencers” — independent Spanish-language journalists in Latin America and Spain — to spread disinformation.

A Cuban-American Miami resident shares one of the sources his mother relies on for her news. Alex Otaola, a Cuban-American social media influencer and political pundit, shares footage of a Russian submarine in Cuban waters on Facebook Live. Photo by Jennifer A. Ortiz for Feet in 2 Worlds

The Associated Press reported that U.S. intelligence officials warned nearly a hundred countries that Russian intelligence was going to cast doubts on the integrity of elections happening all over the world in 2024. Russia is also helping spread the false narrative Ferro heard on the radio, about rising crime in the U.S. being committed by immigrants.

This disinformation and misinformation circulates among Americans regardless of where it comes from, and as Ferro said, impacts how voters approach issues on the ballot.

“When you are going to vote in an election, that you have to vote, not based on your principles or for what you think is best for you (and) for your family, but from an unfounded terror, absolutely sick and false, that you have in your head…” Ferro said, “...it’s terrifying.”

—

This series is based on original reporting by investigative reporter Martina Guzmán. Logo design by Daniel Robles.

Stanford University journalism students Janelle Olisea, Eve Lu, and Xavier Martinez contributed to this report, as well as Irene Casado Sanchez, Big Local News data journalist.

Feet in 2 Worlds is supported by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, The Ford Foundation, the Fernandez Pave the Way Foundation, an anonymous donor and contributors to our annual NewsMatch campaign. The Fund for Investigative Journalism provided funding for this project.

Paulina Velasco is a multilingual journalist based in California. She has made narrative documentaries and interview shows for 10 years for a variety of outlets, including Marketplace, LWC Studios, Slate, Pacifica Radio and NPR member stations. She writes for The Guardian about immigrants’ experiences in Southern California and particularly at the San Diego-Tijuana border–just 10 miles from where she grew up. Paulina was also the editor of the inaugural season of 100 Latina Birthdays, an audio documentary series about Latina health in the U.S. Her political science education helps her interrogate structures and policies, and her curiosity and empathy empowers her to accurately portray the lives of people who are often misrepresented in the media. She has lived in Mexico, France and New Zealand, and loves reading books by Latina authors — a group she one day aspires to join. Portrait by Las Fotos Project. @_pinavelasco

Jennifer A. Ortiz is a Cuban-American photographer and graphic artist born and raised in South Florida. Her work explores environments, trauma, healing, identity, histories and memory.

John Rudolph is the founder of Feet in 2 Worlds, a leader in centering immigrant voices in journalism. Created in 2004, Feet in 2 Worlds (Fi2W) is an independent media outlet, journalism training program and launchpad for emerging immigrant journalists and media makers of color. Fi2W brings positive and meaningful change to America’s newsrooms and has a broader impact on how immigration is reported and the ethnic and racial composition of news organizations. Over nearly five decades in journalism John has covered events in the U.S. and around the globe with a special focus on immigrants and immigration, U.S. politics, and environmental issues including climate change, population growth, and industrial pollution. His work has been honored by numerous journalism awards.

Martina Guzmán is the director of the Race & Justice Reporting Initiative at the Damon J. Keith Center for Civil Rights at Wayne State University Law School in Detroit, Michigan. Her reporting covers immigrant communities and systemic inequality. She was named Best Statewide Individual Reporter by the Associated Press for her work at WDET, Detroit’s NPR affiliate. Her exploration into the rise and fall of global, post-industrial cities earned her Best Investigative Series from the Michigan Broadcasters Association and the Associated Press of Michigan. Martina was the Detroit correspondent for The Takeaway, a radio news program by Public Radio International and WNYC. She has received numerous grants and fellowships, including the MacArthur Foundation, the German Marshall Fund and a Ford Foundation, to investigate the impacts of water shut-offs on women of color in South Africa and Detroit. She is a graduate of the Journalism School at Columbia University in New York City and a 2023 John S. Knight Journalism Fellow at Stanford University.